| Fra de Dadá, figura carismática da Praia, morre aos 84 anos |

|

| 21-01-08 |

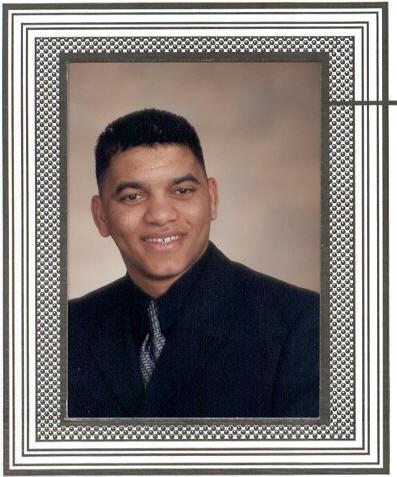

Alfredo Barbosa Amado, Frá de Dadá, figura carismática da Achada de Santo António e da Praia, onde viveu durante largos anos e onde lhe nasceram parte dos seus 31 filhos, morreu no passado dia 14. Polícia, desportista e comerciante foram algumas das actividades desenvolvidas por este cabo-verdiano de sete costados. Deixou 31 filhos, entre eles o autarca Aqueleu Barbosa Amado (Santa Catarina, ilha do Fogo), bem como o antigo comandante da POP, Abailardo Barbosa Amado. |

| Na Praia, sobretudo no mundo do desporto, não havia quem não o conhecesse. Aliás, foi graças à sua paixão pelo futebol que o mundo lhe abriu as portas quando, jovem ainda, tornou-se guarda-redes na sua ilha natal, Fogo, da equipa dos Nazarenos. Agente da antiga Polícia de Segurança Pública haveria de ser transferido depois para Praia, Boa Vista e S. Vicente. Na Praia, pelo menos, alinhou pelo Sporting. Reformado dessas lides, tornou-se árbitro de futebol. Além de polícia, Frá de Dadá foi também operador de máquinas das antigas Obras Públicas, dando ao mesmo tempo os primeiros passos na actividade comercial, actividade essa que haveria de preencher o resto dos seus dias, até a idade de 84 anos. Alfredo Barbosa Amado deixa 31 filhos, 79 netos e 17 bisnetos, além da viúva Maria Felícia Monteiro, que completou 78 anos no passado 15 de Janeiro, um dia depois do “passamento” de Frá de Dadá. A este homem íntegro e intransigente na educação dos filhos, um foguense que nem os largos anos da Praia tirou o vulcão e o sentido de honradez de um bom filho de Djarfogo, «A Semana» rende a sua mais sentida homenagem. À família enlutada os sentidos pêsames desta equipa, que todos continuem a honrar o legado de Frá de Dadá. Fonte: http://www.asemana.cv/article.php3?id_article=29092 |

Friday, February 08, 2008

IN MEMORIAM ALFREDO BARBOSA AMADO (in A Semana)

Wednesday, February 06, 2008

Review of Dorothy White "Black Africa and de Gaulle"

Black Africa and de Gaulle: from the French Empire to

Black Africa and de Gaulle: from the French Empire to (Picture: General de Gaulle and Governor Eboue in Chad during World War II)

No other French president had had much impact upon

De Gaulle relative political position to

When the tide of the war began to change, it became necessary to reward the Africans, who had given sweat and blood for the sake of

From 1946 to 1958, de Gaulle remained out of active politics through self-imposed a political retreat to Colombey. This did not mean that he kept himself away from the news of the political game. White argues that de Gaulle was pretty much kept informed of all the crises and other political games of capital importance that were taken place in France and in her empire. During his stay of active politics, a lot had happened regarding the political configuration of the African colonies. Africans were now thinking more in terms of their political Africanity instead of their supposedly French Africanness. Among the most important event, the Loi Cadre of 1956 provoked important political consequences in

The 1958 crisis, one of the many political crises of the

The book, however, does not delve into the post-independence linkages between de Gaulle and black